- A lot of sports fans are looking forward to the possibility of watching sporting events using immersive technology like virtual reality and augmented reality, but few know how far along it is.

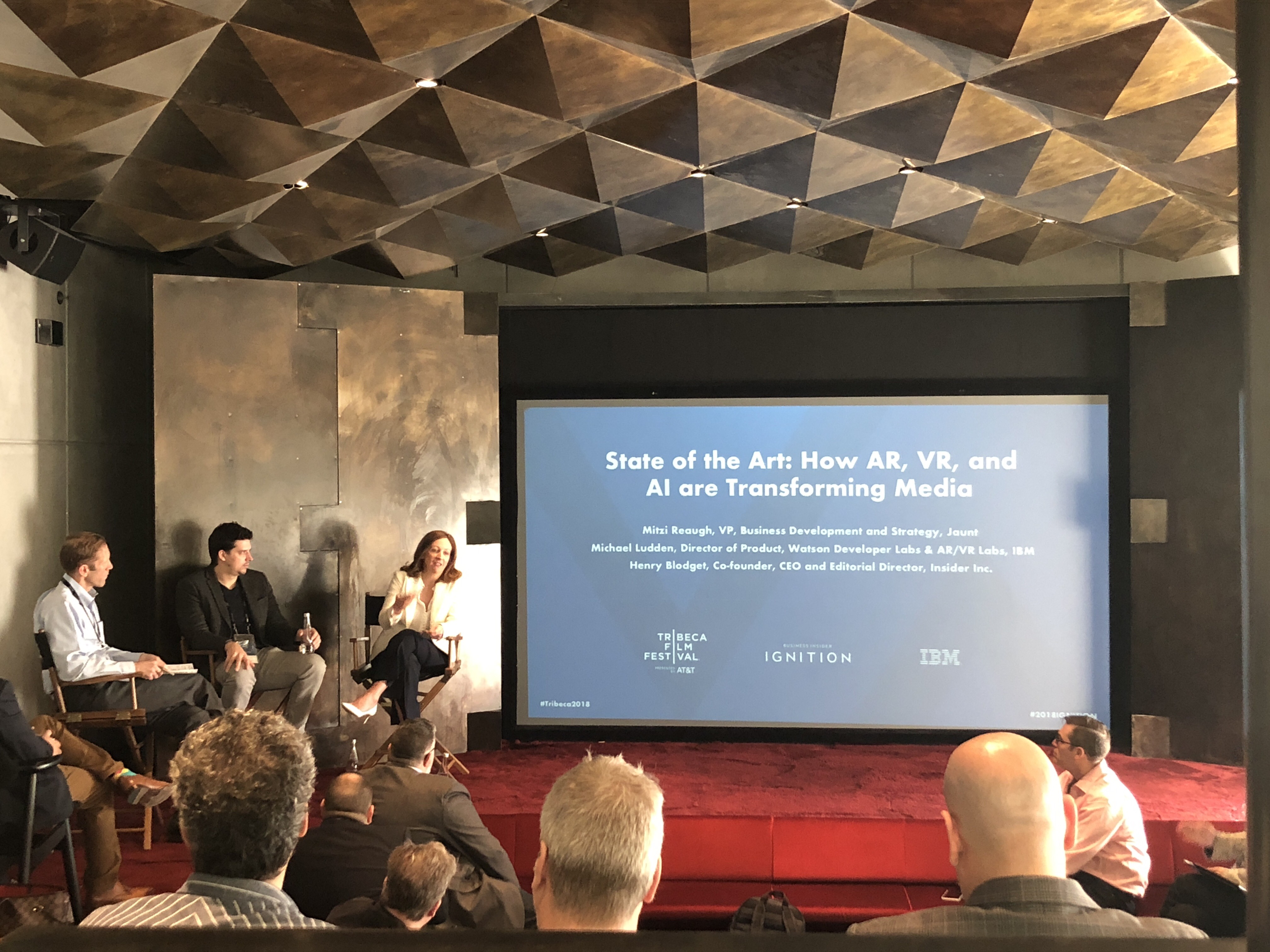

- At this year’s Tribeca Film Festival, sports fan and director of product for Watson Developer Labs & AR/VR Labs at IBM Michael Ludden talked about the obstacles facing VR and AR in sports, during a panel moderated by Business Insider CEO Henry Blodget.

- Also participating in the panel was Mitzi Reaugh, VP of development and strategy at Jaunt, who brought up some alternative use cases that show how AR and VR could be here sooner than we think.

Among the many opportunities presented by virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR), people are really excited at the prospect of being able to wear a headset and feel like you’re courtside at a basketball game, or on the sidelines at a football game, all from the comfort of your own home.

This interest hasn’t gone unnoticed by leaders in the industry like Mitzi Reaugh, VP of development and strategy at virtual reality company Jaunt, and Michael Ludden, IBM’s director of product for the company’s Watson Developer Labs & AR/VR Labs.

Reaugh and Ludden discussed the role immersive technology is playing in media during a panel moderated by Business Insider CEO Henry Blodget at the Tribeca Film Festival this week.

"You guys do some of this, so I don't want to throw anybody under the bus," Ludden said, referring to Jaunt's technology. "But I would say that it's not quite there yet in terms of usability."

Today, VR for sporting events is extremely limited. Users can't watch live games. Camera positions are limited, there's no ability to zoom, and production quality is nowhere near what traditional broadcasters are able to provide.

"I'm a sports fan and I've tried a number of these things, both using Jaunt and other platforms, and frankly for the most part, it's pre-digested 30-second clips," said Ludden.

The biggest obstacle is what Ludden referred to as an "incentivization mismatch," since sports arenas and stadiums actually want people in the seat and paying for tickets, merchandise, and snacks. It's similar to the tension that's existed with broadcast television for decades, except that stadiums might even be asked to forego seats for VR equipment to sit in.

For what it's worth, Jaunt doesn't participate in virtual reality for live sports, and while Reaugh agreed that it's an underwhelming experience, she did argue that it's on it's way. Other immersive technologies like augmented reality are well on their way with live sporting events.

At one point, Reaugh showed off a picture of a 3D replica tennis match being projected onto a table, and it was met with sounds of intrigue from the room. Similarly, she said consumers would soon be able to project athletes onto a table ("a Princess Leia thing") and surround the projection with the athlete's statistics.

"It's a complementary experience to linear television, but also a unique experience."

For people in the stadium, there's also an opportunity to provide headsets that overlay statistics or commentary. Stadiums would be on board, since it would give them the competitive advantage of providing fans just as much information as they would get from their TV.

The tabletop projections are currently in the research and development stages, and the consumer cost is "TBD," but Ludden estimated that AR headsets in stadiums could be available as early as this football season.

As for virtual reality, he's still hesitant about the execution, but expressed a hint of optimism. "I think we'll get there eventually because there's a demand and there's a use case."